Marcus Bergman - 2025

The Fredrik Roos Foundation awarded Marcus Bergman the scholarship with the following citation:

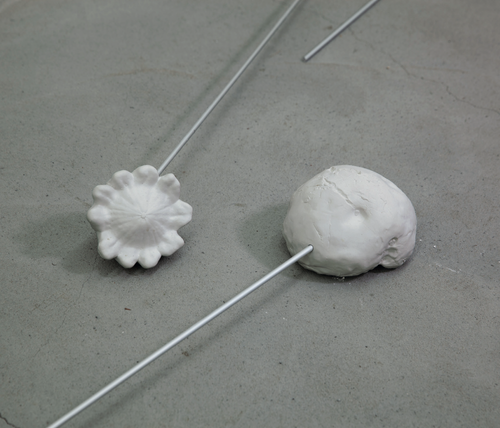

"Marcus Bergman's works bear witness, both conceptually and materially, to an artistry of complexity and depth. With meticulous craftsmanship, he creates sculptures that – through their physical existence – demand the viewer’s gaze. The works possess a strong physical presence and touch upon universal themes such as mortality and suffering. However, it is almost impossible not to feel tenderness for these works, which in their motifs radiate love, queer identity, and a tangible fragility.”

It is with great pleasure that Museum Director Bo Nilsson welcomes Marcus Bergman to Artipelag with the exhibition Intimate Destruction. The exhibition includes a number of new works and is accompanied by a catalogue presenting Bergman's artistry.

About the Artist

Marcus Bergman was born in Mölndal in 1993 and is currently based in Stockholm. He received his Master's degree from the Royal Institute of Art in 2024 and his Bachelor's degree there in 2022. His artistic education also includes studies at Gerlesborg School of Fine Art, Pernby’s School of Painting, and at the University of Gothenburg in Art History and Visual Studies.

Bergman's work in recent years has been characterized by a figurative expression based on the human body. The works appear as reliefs and sculptures, created in wax and incorporating other materials such as polyester, steel, and wood. They carry a complex thematic revolving around inherited pain, annihilation, tenderness, and queer identity.

For his work, he has received several grants, including those from the Ragnar and Hilma Svensson Donation Fund (2024), the Helge Ax:son Johnson Foundation (2024), and the Gustaf & Ida Unman Donation Fund (2023).

Frida Peterson - 2024

This year's Roos grantee is Frida Peterson, who created an artistic mixed form consisting of a wild flora of artistic and less artistic materials that she treats with great respect. Perhaps one can guess that her knowledge of the arts and crafts constitutes an important dimension, a slowness that calls for reflection. However, it would be wrong to claim that Frida Peterson's artistry would only be craft-based. In her work there is also a conceptual dimension. Her art approaches questions that oscillate between aesthetic and spiritual reflections, which are common in contemporary art.

This applies not least to her graduation exhibition from the Royal Academy of Arts in Stockholm in 2023, where she let a flock of birds from Skeppsholmen's fauna take over the exhibition space with her peculiar choreography. The spirits also invaded her ingenious reconstruction of Sigurd Lewerentz's iconic brick altar from Klippan's church. It also came to articulate the relationship between nature and culture as one of the great destiny issues of our time. We warmly welcome Frida Peterson to challenge Artipelag's identity.

IN CONVERSATION WITH FRIDA PETERSON

Adam Rosenkvist: Congratulations on the Fredrik Roos scholarship! A common thread in your works is that they seek elusive aspects of existence in the familiar and everyday, and in nature. I feel that the works playfully close the distance between earthly life and the great unknown, until only a thin, almost imperceptible membrane separates them. I am particularly thinking of your graduation exhibition, The Holy Spirit. In it, a flock of curious birds, made of papier-mâché and fabric, strolled around a full-scale copy of Sigurd Lewerentz's altar for Sankt Petri church in Klippan. How did you find this theme?

Frida Peterson: Thank you! I am so very happy and honored. My thesis came about through parallel impulses. First of all, I am very fond of birds. During my master's I spent a lot of time walking around central Stockholm. During the winter months, I used to stop and drink coffee at a feeding station opposite the Royal Palace and watch as ducks and waders partied. For me, watching birds is triggering. They are present, corporeal, often close and at the same time inaccessible. Seabirds move on the border between worlds: the water, the sky and a feeding station at the castle.

In Sigurd Lewerentz's church in Klippan, the lampposts stand with bent necks and bow slightly. The altar is as big as a thick carpet and built in a functionalist style – an altar that must fulfill a function and it too is on the border between worlds. Before I started my master's I lived in Malmö and had some kind of crisis. Or maybe not a crisis, more a time of boredom and inactivity. Maybe I was starting to feel old, or like a confused artist. When my grandfather passed away, I went to Böda church on Öland to listen to the soul ringing.

Böda is a small rural town with a shortage of priests, so the service was held instead by an old pilot. I enjoyed his sermon and thought about what I would talk about if I had the chance to preach. Some years later, I contacted priests in Malmö and had studio conversations. Like Lewerentz's lampposts, I had been struck by a longing to bend my neck a little and I became curious. A source of inspiration for my graduation exhibition was also Giotto's fresco Sermon on the Birds (executed ca. 1297–1300, ed. note), which depicts Francis of Assisi preaching to a group of birds.

Adam Rosenkvist: The studio conversations with the priests must have given many unexpected angles to your practice. It is also so obvious that you have studied the everyday comedy of the birds: how they move, gesture and relate to each other as a group - almost like a Bruno Liljefors painting in sociological vintage! As I have looked more closely at your sculptures, I have noticed that you constantly emphasize the stitches, the brush strokes and the materials. You thereby underline the creation process of the works and the handwork they have emerged from.What does your process look like? And what knowledge is in the hand?

Frida Peterson: In my work, I like monotonous movements a lot. When I learned to knit many years ago, I was told that the trick was to find a rhythm and not focus on the single stitch. One movement must in a self-confident way give power into the next and only when you have found the rhythm will it be good and the work will then knit itself. It is such a good description of many craft techniques and runs through almost everything I do. My background is in textile craft, which I have studied for many years. In recent years I have worked with a greater variety of materials than just textiles, but I think I have brought the pace of these techniques with me. Because when I reach that rhythm, my head is empty and I can work for as long as I want. My process often starts with me getting hooked on something. It can be something I find beautiful, interesting or that tingles. And then I think I should work on something completely different. Something more thought out and well planned. But it doesn't work. This, combined with the fact that I find a material and a technique that feels stimulating, means that I start working.

I think I work a bit like a weaver. The weaver builds his image from the bottom up, much like drawing a picture from one side to another. I don't really know how the composition or the whole will be until the end. One thing leads to another and slowly a mood, a theme, a scene is born. It's so hard to create something that feels like it's still alive when it's finished. Sometimes when I've planned a piece of art in advance and execute it according to plan, I can be hit with the feeling of having held something alive and warm in my hand , but that on the way I have squeezed the life out of it. The starting point overcomes the work. I feel that I come closer to something alive if the idea feels embarrassingly unclear when I start and I sometimes try to understand what it is. I want to continue to look at it with wonder and not as an illustration of a process that is already over.

Erik Uddén - 2023

"Erik Uddén connects finished wall fragments with different texture and materiality with plaster treatments and painterly brushstrokes into new combinations, where you never really know what are the random harvests from the material's previous life and what the artist has added as a conscious act. It is in this open situation that the viewer feels invited to a dialogue. Uddén allows his paintings to be connected to both walls, ceilings and floors and sometimes the occasional window. In this way, the installations are part of a close dialogue with the architectural space, and thus the connection to society also feels like a natural part.”

The scholarship exhibition takes place in various locations at Artipelag, such as the entrance hall, on floor 1 and on the so-called "Björn's floor" on floor 3. The exhibition has free entry and also includes a catalogue. 2023 is the sixth year that distribution and exhibition will take place at Artipelag.

About the artist

Erik Uddén was born in 1990 and grew up in Söderhamn, Hälsingland. He is currently both working and living in Stockholm. Uddén completed his master's degree at King's College. The Academy of Arts in Stockholm in 2022 and his bachelor's degree at the Academy of Arts in Malmö in 2020. He has previously studied at Pernby's painting school and the Art School in Gävle.

Uddén has been awarded scholarships from the Art Academy (R. and H. Svensson's donation fund), 2022 and Karin and Erik Engman's scholarship in Gävle in 2018. His work has been shown at the Mazettihuset in Malmö, the Art Academy in Stockholm, Sandvikens Konsthall, Bollnäs Konsthall and Galleri Bo Bjerggaard in Copenhagen.

Uddén works with a painting that dissolves contours between sculpture and painting, where the tension frame and the canvas are often used as sculptural forms. He uses color to negotiate and transform a variety of materials, conventional as well as unconventional. In Uddén's work, the ambiguity of the painting is examined as both window and body to navigate the room.

Judit Kristensen - 2022

In Judit Kristensen's paintings, it is hard not to think about the pandemic that we have just lived through in the last two years. But her paintings are not imbued with a sense of the desperate loneliness that characterized the spirit of the time. On the contrary, Judit Kristensen's paintings are characterized by a coldness that gives them an almost observational and analytical character. This does not appear to be particularly surprising given that Judit Kristensen trained as a psychologist at Umeå University before her artistic education. Her almost clinical approach to these emotional states testifies to a deep knowledge of the human psyche.

It is with great pleasure that we award Judit Kristensen the Fredrik Roos Scholarship and welcome her to Artipelag.

IN CONVERSATION WITH JUDIT KRISTENSEN

Iselin Page, Curator Artipelag:

Congratulations on the Fredrik Roos scholarship! It will be very exciting to work with you and get to know you and your artistry. One of the first things I wanted to ask about, which struck me when I saw your work, is your background in psychology. Before you started studying at the University of the Arts, you studied psychology for five years. What did you take with you from there to art school and how has your interest in psychology influenced your artistry?

Judit Kristensen:

Thank you very much for that, I am very happy and look forward to working with you! I come back to trying to depict some kind of psychological place, a mental space or condition, and there is probably always an existentialist core in the works I want to make, but I don't know if it is influenced by an interest in psychology or by my training. I actually don't think it is. I think it's a difficult question, hard to imagine how one's approach would be without a certain experience or knowledge. And both art and psychology are so abstract, it's hard to tell where one begins and the other ends.

Iselin Page:

It is perhaps understandable that the viewer draws parallels between your art and psychology. To understand an artistry, one often tries to place it in a context that makes sense. When I saw your works, I also thought a lot about the last few years that have been marked by the pandemic. The works appear to be very relevant in their time. Now the pandemic has moved into a new phase, but unfortunately we are experiencing a time in Europe marked by several disasters, most recently the terrible Russian invasion of Ukraine. A war that has shaken the entire European population. Now I'm not going to make this a political question, but I'm still curious if your artistic practice reflects a world-watching approach?

Judit Kristensen:

There is some kind of autobiographical root in the works I make, and I pick up aspects from my surrounding world and time that I think can help me towards something I'm looking for. Since a very young age, I have been interested in some kind of everyday existence that a corona existence has been favorable to. I have been interested both in depicting myself and in taking part in other people's depictions of more trivial aspects of life. When I was twelve I used to take the bus from the village to the city and go to the Gallerix to stand in front of a poster reproduction of Nighthawks by Edward Hopper, and I am very weak for the everyday scenes of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin or the entire artistic output of Matt Bollinger. I don't really know why I want to portray that kind of existence. I've thought about it and wondered if I wish I could connect the loneliest and dullest aspects of my existence to a collective story told through culture about what life is all about. In any case, a corona existence has been an inspiring existence, haha. I have also long been interested in some kind of mental space, trying to depict claustrophobic, ambiguously threatening private home environments or sleep problems and the experience of days and nights flowing together, which the corona era has also been favorable for. But apart from that, I don't know if I have a particularly world-watching approach, it's not something I'm looking for anyway.

Apart from the fact that there is of course an awareness that a work of art relates to an environment and is understood in a context, which I think all cultural practitioners have some sort of understanding of. I sometimes think that I might leave something that others understand based on their personal experiences and associations, and I think that's very nice, like that a special artistic communication can exist, and a social context or worldview is something you have to understand that a viewer will be influenced by in the perception of a work.

Iselin Page:

In addition to your motifs and themes, I also really like your style and have especially noticed the large open areas in the drawings and the color palette in the paintings. Looking at your older works, it still feels like you found your style quite early in your artistic career. I would like to know a little more about your interest and approach to painting and drawing. Have you always been interested in expressing yourself visually?

Judit Kristensen:

Thank you so much, how nice to read it. Yes, I have. My ten years older sister used to tell me that I drew so much as a baby that at ten she was afraid that her little sister had been born insane. Apparently I mostly lay on the floor manically producing drawings of horror vacui compositions of cephalopods, with a devotion and a pen grip that she used to say looked absurd for a baby who could barely walk, and she apparently tried, unbeknownst to my parents, to keep me away from pens and paper because she was so worried about my mental health, haha. As a child I also used to cut a lot from colored paper and make visual stories, and I always appreciated a pen and paper if language felt insufficient.

I have also long had a very great admiration and perhaps excessive romanticization of visual communication. Something that was significant for me was finding my first two favorite artists. I found the first one when I was twelve, browsing the backs of a record store. I had just discovered music and was pretty geeky, and I saw the artwork on the cover of Cherry Kicks by Caesars Palace. There was a girl in the background on the cover doing something I didn't understand but still felt a strong connection with, which opened the door for me to what frequencies something visual can communicate within. I bought the disc so I could keep watching it. When I got to the girls' room, I realized that the drawing was bad, according to the measuring instruments I was taught by my art teachers. The heads were too big, the feet too small, the girl in the background that I was enchanted with seemed to be sitting but had no chair. I was annoyed, because I remember having the feeling that the artist knew the hands were too small and had left it at that.

I kept looking at the cover I had spent my weekly money on, and after a while I got the feeling that I understood something my art teachers and maybe the whole adult world didn't. Something visual could offer a magic that was not equated with anatomical correctness, there was something else that was the goal, something else to chase, which I have no idea what it is, but I've probably been chasing it ever since, and I I hope I can do it for the rest of my life.

The second favorite artist I found was the illustrator of the children's books about Sailor and Pekka. I used to read them as a young teenager to my niece and was captivated by the cartoons, I think we both were. It made me make my own adventures also about me and her. One day it occurred to me that I had two favorite artists and was perhaps interested in art, and that I should learn their names, at least see who they were. I first looked at the children's book, it had been made by Jockum Nordström. Then I opened the CD and looked in the little booklet, and when I read the same name I couldn't believe it. It felt so absurd to have picked the same person out of the multitude of visual impressions the world offered. For you and me now it is of course logical to recognize an artist in different contexts, but for me as a twelve year old it felt like magic that my two favorite artists were the same person. It built some kind of alliance between me and something I thought I was alone in finding, a teenage self-confidence and protection against self-censorship, it was significant.

Iselin Page:

What a story and experience. It makes so much sense now that you watched Jockum Nordström when you were young. It's also great fun that you can trace your interest in art back to childhood. As a final question, I'm curious about where the road goes next for you. What does the future look like and are there any ideas or projects you would like to share?

Judit Kristensen:

How nice, thanks for that. Yes, teenage idols are important, I think. I'm glad for the ones I had. I've been living in Antwerp since October, I'm happy about that, I have a studio and an apartment that, apart from the occasional hour at a bar, I go between. It's been a pretty nice life. And the occasional trip to exhibitions. Antwerp has an exciting art scene. I was curious about it from Sweden and now I'm happy to be part of it. I will probably spend some time here before I come back to Sweden. Antwerp is also so nicely placed in Europe. Today I've been in a town called Aalst and left paintings to a private art gallery for a group exhibition that has a vernissage this weekend, which should be fun to be a part of, and the day after it opens I'm going to Sweden to hang an exhibition at Örnsköldsvik's art gallery, which I'm looking forward to. But unfortunately both of these exhibitions are probably old news by the time this publication is printed. A future plan that is planned for the week after the exhibition at Artipelag opens is an exhibition in London, with a group I am very happy to be a part of, but at the time of writing it has not been announced yet. And after that, most projects I look forward to are sadly "unannounced". But I hope that the future means that I get to continue working with art, and I am truly forever grateful for how the conditions for that have improved thanks to this scholarship.

Siri Elfhag - 2020

"The Fredrik Roos Stiftel's scholarship in 2020 is awarded to Siri Elfhag for a painting with close ties to European art history. Her work has a tendency to leave the corporeal and float out into a universe that is close to the interface of surrealism between the dreamlike scenery of the external and digitized reality. The paintings give a feeling that painting is dissolving itself from within in a changeability that is related to the figures of the expressionist tradition.”

In conversation with Siri Elfhag

The following conversation took place as an email exchange between Siri Elfhag and Iselin Page, 2019.

“What can I say, O dear art lovers, O kind-hearted dreamers? Need help? Doesn't the painting say it all? What am I looking for? A long time ago I said that I wanted to seduce through imperceptible movements from one reality to another. The viewer is caught in a net and can only break free by walking through the entire painting until the exit is found. My greatest desire: to create a trap from which no one, neither you nor I, can escape.”

- Dorothea Tanning, 1986

It is the month of December and the winter darkness has settled over Stockholm, but it doesn't matter for Artipelag has just received the colorful news that the Fredrik Roos Foundation has appointed Siri Elfhag as the year's scholarship holder 2020. Time is short to produce an exhibition and a directory and we immediately contact Siri. Two days later we will meet at Café Kafferepet in central Stockholm. Surrounded by pensioners, we sit there each with an almond cake and a cup of coffee to discuss the upcoming production. We decided to follow up the meeting with a digital exchange of letters that can later be published in the catalog to include Siri's voice. After the meeting, the curiosity about Siri's work and process has become stronger and I get the feeling that there is a personal depth in her paintings that I want to explore. The ball is in my court, and I send my first question to Siri.

Iselin Page:

I feel that your paintings possess a sensitive power that makes me see my surroundings differently. I immediately think of how an emotionally inclined painter allows his painting to reap the fruits of personal experience. You yourself describe your artistry with words like "emotional cannibalism". To what extent do you use your personal experiences such as relationships, dreams or fantasies in your works?

Siri Elfhag:

I am inspired by everything that has ever happened in my life and other people's lives, and by man's countless attempts, with mixed results, to deal with and process these events, transforming them into something "good". I think a lot about evil and what it looks like inside different people, what colors it could be. And if everyone's private perception has anything to do with reality. Images we carry with us quite involuntarily, inner symbolic landscapes for which we hardly know who is responsible. Something I have worked with almost consistently ever since I started painting is a theme that was first unspoken and then named "emotional cannibalism". I think I've been working on the same thing all along, actually before I started painting as well. Maybe as far back as when I was a child and playing. Often I played family or relationships, it could be anything, any objects or objects that were part of different kinds of relationships. And I played the same kind of games over and over again. The one who seeks contact and the one who answers, accepts or rejects. I remember the day I stopped playing, I was 12 years old. And picked up my barbie dolls to once again start a game that suddenly felt unnatural, artificial.

"We played with barbies, where we put on and took off their sunglasses so their wide eyes made us cringe."

It didn't work anymore. I was struck by sadness and a need to create grew instead, to be able to evoke the same type of scenes that once took place in the game, but this time in words and images. I drew and wrote. And in the last year of preparatory art school, I started with oil painting. From the beginning I thought that my painting was not about anything, that it was just different attempts to master the brush or paint. But then I started to see stories in the pictures that seemed to fit together. Relationship stories. And just as from the very beginning, it is not only relationships between people, but also between animals or objects, dead things that live. And what they are all dealing with is a desperate, eternal quest to try to meet, be close to each other and understand each other. Even if it's the forest trying to get along with the beasts or whatever it is that plays in it.

Iselin Page:

As a viewer of your works, I can't help but see myself exactly as you describe the motifs, in an eternal quest to try to meet, be close and understand. It is as if the works convey a strong sense of a narrative. I am invited to a landscape of stories that

I can never really understand. Can you recognize the description that among your surreal elements rests something mysterious and enigmatic?

Siri Elfhag:

In my work, in art in general or perhaps in everything, the mysterious is also the most indispensable. Someone described my painting as the motifs "morphing" in and out of each other and never really standing still. I am interested in how external and internal images interact or conflict with each other, both when it comes to our actual seeing and what emotions we add (perspective) that affect the appearance of things. Not being able to really understand, as you say, is also what makes sense to me. If something has too definite a shape, I want to loosen it up. There is a story but at the same time it can sometimes seem impossible to handle. Managing feels like control, and I don't want that. I am also constantly practicing letting go of the need to preserve or own my images and to not take what appears too personally. Letting them come and go as they please and instead be surprised by what sticks on the screen, which is difficult.

Iselin Page:

It is interesting to read when you talk about the emotional and personal behind your works, but I would also like to know more about your process, method and choice of materials. I perceive you and your artistry as very open to expansion through a continuous development that is not limited to painting. How do you relate to the different disciplines you work in? Do you have a specific process or working method that you want to tell us about?

Siri Elfhag:

I would describe my work process as working with layers, where different picture stories are first formed for the upper and lower layers of consciousness and then my attempts to transform these on the canvas. Therefore, the paintings also almost always consist of very many layers that have been applied gradually. Sometimes I work on a painting for several months, sometimes for a few hours. Often I paint over existing paintings and sometimes also other people's paintings. Several of the works I did at art school were originally found works by a deceased hobby artist whose belongings were to be thrown away. I took care of some of the paintings and used their motifs to create new ones. When I made the Dream Book, I used the app Instagram as a tool. From the massive flow of images, I collected hundreds of images of mainly historical paintings or photography. Then I made a kind of intuitive selection. It could be a color or a contour, a shape that "felt good" for the moment. I didn't study the pictures I chose right away, but looked at them briefly and kind of photographed them from memory, as I think most people do without thinking about it. With a vague memory image as a starting point, I then drew something else. Something I discovered with this method was that when I went back to the original image, after the drawing was completed, there was always something, some element that marked the events of the day. A kind of key to unlock the subconscious and access another layer of myself.

Iselin Page:

Even though you are a recent graduate, you already have a sureness of style and maturity in your works that make the mind flow towards a Central European and American painting tradition. When I look at your work, I immediately think of artists like Willem de Kooning and Dorothea Tanning. I get the feeling that there are international influences and a strong painting tradition at the art school in Umeå. What have five years at that school meant to you in your artistic development?

Siri Elfhag:

When I was admitted to Umeå, there was a lot of painting at the school and a tradition of painting as you say. But during my years of study, teachers were continuously changed and I felt perhaps that the only fixed point in the end was the building itself. I probably also retreated to my own studio quite a lot. Socially, I would say that the time in Umeå has influenced me the most. Without the people and events that took place there, no art would have been created either. Umeå has sometimes seemed more surreal to me than the paintings I made. But in the end, perhaps all contexts are equally incomprehensible.

Read more about:

Siri's artistry: http://www.elfhag.com/

The exhibition: https://artipelag.se/utstallning/fredrik-roos-stipendium-2020

Sara Nielsen Bonde - 2019

The foundation's justification reads:

"Fredrik Roos foundation's scholarship 2019 is awarded to Sara Nielsen Bonde for an artistry that starts from a tradition that breaks up a classic dichotomy between nature and culture. Nielsen Bonde uses a double movement between nature in the landscape and when she brings nature into the space of art. Her work plays with our notions of what are authentic experiences and what are cultural notions and touches on several relevant questions about nature, culture and climate."

Biography of Sara Nielsen Bonde

Born in 1992 in Sønderborg in Denmark, lives and works in Stockholm.

Sara Nielsen Bonde has devoted herself to art and architecture since 2011, when she began studying at BGK Syd at Sønderjyllands Kunstskole in Denmark. The following year, she continued to study architecture at the Academy of Fine Arts' School of Architecture in Copenhagen. After careful consideration, Nielsen Bonde nevertheless decided to discontinue his architectural studies and instead focus on his artistic practice. In 2014, she entered the five-year program in liberal arts at Kungl. The Art Academy in Stockholm, where she will take her degree in spring 2019. During the five years at Kungl. At the University of the Arts, she has been drawn to places with a close connection to nature. This has led to several trips to southern Denmark and two semesters abroad as an exchange student, one in Norway at the Kunstakademiet in Tromsø and the other at Iceland's art school, Listaháskóli Íslands, in Reykjavik.

During her studies, Sara Nielsen Bonde has participated in national and international group and solo exhibitions, for example Fossils from Future, 2016, at the Museo de la Ciudad de Querétaro in Mexico. Her most recent exhibitions include a group exhibition in Helsinki in collaboration with fellow students on the master's program, and her graduation exhibition Outer Bark, Inner Wood at Galleri Mejan in Stockholm.

After graduating in 2019, Nielsen Bonde plans to move to Gothenburg where she will continue her artistic work.

Read an interview in Nacka Värmdö Posten with Sara Nielsen Bonde here >>

Jonas Malmberg - 2018

"The 2018 Fredrik Roos foundation scholarship is awarded to Jonas Malmberg for an artistry that is based on a Nordic, romantic tradition - a tradition he problematizes in an extremely intelligent way."

INTERVIEW BY JONAS MALMBERG

Iselin Page – Curator, Artipelag

Although you are a young artist who has recently graduated from art school, your works testify to a mature process that is focused towards an expression and towards specific materials. The color palette returns and the motifs slide into each other. Your collages and your painting have the same foundation and are installed without hierarchy in relation to each other. I perceive you as an artist who immerses himself in one thing for a long time, therefore I want to start by asking what your artistic process looks like?

When I start working, I have a sense of which direction I want to go and then it's like a negotiation about how to get there. First I paint something that I don't think quite right and paint over it, then I think "no, it was probably pretty good actually" and try to scrape out the old one. I have given up the idea of making a sensible basic drawing, which I used to be very careful about. That's why I started chalking, because it goes faster. I work in parallel with different things all the time; when I'm in the studio I paint and at home I sit with my collages in front of the computer. Often I work for as long a period as possible, mostly to filter out my own spontaneous impressions. It probably has to do with the fact that I find it difficult to see myself as an original thinker. I come up with things little by little, remove something and add. I see something in town or read something and think "maybe that wasn't so stupid" and then I take it in; it is a constant renegotiation. I also set up what I'm working on around me to see if it works at scale. Often I paint for a very long time on different parts until I think it works. I can easily get stuck in a corner and paint very carefully on any detail. Maybe no one even looks at that part anymore.

What makes a work work or not?

I have come to the conclusion that it is sound. When the paintings don't work, it's like lots of flickering noises. Then I try to work until it has solidified completely, until it has become quiet. It might sound a bit strange, but I want the paintings to have different tempos, not to be completely consistent. I want certain processes to go 23 ISELIN PAGE Superintendent, Artipelag TIME & PLACE June 2018, Malmö ARTIPELAG fast so that it stands in contrast to something that has taken a long time. Then they must meet and harmonize, so that it becomes quiet. It's hard to get any closer than that.

There is something very dark in your works, not only in the motifs but also in the color palette. The gray scale against the dark green and blue reappears in all your paintings and collages. What is it about the dark that interests you?

This obscure expression has probably been partly created because the model is usually quite rigid. I think it has arisen as some kind of contrast to my collages, which are quite hard. I print collagen in grayscale because I want to come up with the colors myself, I want it to be soft. A color often wanders out of one painting and into another, they belong together so far, even though I see each painting as a work in itself. The darkness helps me harmonize the paintings. Each one is its own reality or its own form, but there is something obscure that they all carry. It just gets darker and darker every time I paint. I have realized that there is something there that right now feels very important. There is something in this darkness that feels safe.

Your digital collages began as templates for your paintings, but have evolved into works in their own right. Do you still see collagen as a first stage, as a preparation for painting?

The collage started as a tool before working with the paintings, then I became interested in collage as an expression in itself. I realized after a while that I had been doing it for years without reflecting that it came so naturally. The collage Boardwalk (p.16), for example, I didn't think would become a painting from the beginning, but it turned out that way. In the studio, I don't treat collagen with silk gloves, it stifles all forms of creativity, so the work is quite damaged. Yes cut it up and scanned it into different pieces and then put it back together digitally.

Tape often returns in different ways. When I look at your collages, it seems obvious that the tape comes from there, because it has a function and holds the pieces together, but the tape also appears as a material in different contexts, both in and around your collages and paintings. How did tape find a place in your works?

I use a lot of tape. It's partly because it's fast, I don't want to think too much. Once I get an input, it has to go away. It's about working at different paces, one month I can work for a very long time with a painting. In between, I think "I can't take it, I'm going to screw this up", and then I put the painting away and try to put something else together very quickly. After all, both are equally important and everything forms some kind of whole in the end. The composition contains different tempos and there is something very fast in the tape that I keep coming back to. Lately, I have also used a lot of tape in exhibition contexts, which means that there is a change of pace in the works. The paintings are made on wooden panels and are quite heavy, they will last for a long time. The tape, on the other hand, only survives the exhibition. It becomes like different time spaces, next to each other. There is something about it that appeals to me and that I think is important.

There is a duality in your works that is interesting and is highlighted by the contrast between the materials, what remains next to what disappears, or the digital in relation to painting. This duality also exists to a certain extent in your motifs, in the constructed combined with the natural, or the abstract side by side with the figurative. How do you think about it?

My relationship with nature is very twofold. I mix trees that I have photographed with painted trees standing next to each other. The European heritage of ideas is something I am very interested in; it is a bit of a European specialty to try to control and create one's surroundings. Just this romanticization of animals and nature and seeing spiritual aspects in nature, while we are inside and poking all the time. INTERVIEW 25 To be honest, I love the constructed, like disciplined gardens. Or better yet, romantic gardens that are meant to look natural, but aren't because there's a thought or idea behind it. They are an expression that someone has wanted to create something genuine, but as soon as you have wanted to create something natural, you have actually failed. When I was going to write my application for the Roos scholarship, I thought "what am I doing - I paint animals". It's so easy, but it doesn't have to be if you dare to take it seriously. I don't want to be ironic in my works. I have many defense mechanisms and can be quite ironic in private; then at least I want to be honest when I paint. I want the viewer to take my work seriously. I want to invite the viewer, but I also want to leave a space for the viewer to think for himself. I myself have never liked being written on my nose when I see art or read a book. I don't like megaphones, I like shades and gray scales.

When you talk about the viewer, I get the feeling that you are also talking about yourself. Is it because you act as an observer to some extent, in your artistry?

Yes, it is so. I probably stay on my edge, even in relation to myself. It's hard to switch off, you're thinking all the time. This is how I build my landscapes, they are the result of accumulated impressions over a long period of time. I spend a lot of time sitting and watching, that's probably what takes up so much time. Landscapes have something, a horizon is so simple but it says something, it is an entrance. I can relate to that. There is a start, you invite. I think it is important that the works are inclusive, that they evoke some kind of association in the viewer. As a painter, you usually work by yourself and then you hang up your works. After all, I can't influence how someone perceives the works, I have to trust that they can take care of themselves, that people look at them and feel something. Unfortunately, I can't be there and there is a sadness in that.

Works in descending order:

Boardwalk - 2018

Blue tree - 2018

Horizon (Delphinium consolida) - 2017

On the train - 2018

For more info, please visit Jonas' portfolio.

Oskar Hult - 2017

It is important to stop painting when it is fun, because then the painting will be good, says Oskar Hult about his painting and points out that it is important that the intuition is interrupted in time while the energy remains. It is probably the energy that rubs off on the viewer. The presence and desire for painting.

I find it difficult to put into words Oskar's painting without getting entangled in metaphors. The paintings are mostly non-representational. There is so much here, but so little is told. I tend to fill in and talk about and around instead of describing exactly what I see. But this going around and around is part of painting, it kind of talks to itself at the same time as it addresses its surroundings. Each individual painting is its own imprint, but together they can be seen as a gigantic score.

In his investigative practice, Oskar has for a number of years playfully, and with great presence, investigated painting as a material fate of time. Introspection and reflection are mixed with intuitive decisions and impulsive outcomes. The palette is distinctive with muted earth colors that go hand in hand with bright colours. The brush shows itself with a covering color application that is often pastose. By, for example, cutting out the canvas from a painting in progress, in order to stick it on top of another in the next moment, Oskar works with layers of time and matter in an extremely concrete way. Humor alternates with dystopia, everyday observations meet complex existential reasoning. Faded memories of various sensations, coincidences and experiences are materialized through fragments that are brought together

Nature is a constant source of inspiration for Oskar. One painting is part of a branch, another a weather forecast, a third comments on Onkalo (a constructed cave, where nuclear waste will be stored for the future), a fourth ponders why the seasons seem to come as suddenly every year, a fifth is apparently a blueberry purple hangover.

In a time of important digital image destinies, Oskar's painted surfaces seem ruggedly present, even downright real. The paintings are stored with time and meaning, material sections of a time's destiny. Although they work excellently on the screen as digital substitutes, it is only in reality that the viewer is allowed to take in them in all their materiality. Unlike the digital image, the painting has physical traces of a previous activity. A time capsule that shows both what was and what is. The absent painter becomes palpably present in the painting, here and now.

Text by: Sigrid Sandström

Professor of liberal arts, Royal Academy of Arts

Josefine Östberg Olsson - 2017

When Josefine Östberg Olsson presents a work, it's rarely just about exhibiting something already produced or intervening in one art discussion or another. What we often encounter in the exhibition room itself are instead sculptural traces or props from a kind of staged situations that engage directly in a socially complex context. For her, it's about an art that takes place, in a way that can appear grumpy and irrational, but which thereby also forces us to reevaluate the contexts the work becomes a part of.

In the master's degree work Shift into Racing Strip in the Still of the Night (2016), for example, the public space around Götaplatsen and the parade street Avenyn in Gothenburg was at stake.

At Gothenburg's art gallery, where the exhibition itself was shown, the installation of parts from a car race the artist staged along the Avenyn, which with its 201 meters turned out to be exactly as long as a racing track, made up the installation. The starting point for the work was the different worlds that live in parallel around Götaplatsen, at the top of Avenyn, with on the one hand its art institutions and on the other hand the raggar and car culture that takes over the place on certain days and nights. The sculptural part just inside the entrance to the art gallery's rotunda, consisted of metal details and car headlights that were supplemented every twenty seconds with a soundtrack from a race that was activated by a sensor at the same moment the visitor entered the art gallery. In an almost intrusive way, Shift into Racing Strip in the Still of the Night thereby opened up a new room for reaction, where the installation itself could refer as much to something that will happen as to something that has already happened. Josefine Östberg Olsson is an artist who makes as much use of traditional exhibition spaces and what the viewer experiences there at a given time, as of what is outside the exhibition space, regardless of whether it is the urban public space or another time. That is, one before or one after the time the viewer interacts with the work in the exhibition. When I saw her master's work, I was reminded of what she, after many years of artistic experimentation, presented two years earlier at her graduate exhibition with the paintings Midnight Demon, Scorch Barracuda and Challenger in the Night (2014). The starting point for these car-painted monochromes was a series of broken vehicles, which could no longer be driven. Perhaps we can say that these works mark the artistic zero point that has made her later works begin to intervene directly in the empirical reality outside the art room itself, and at the same time make it part of its form. A form that in this case reflects a tension between different "cultural" worlds in society, without letting the work of art resolve its contradictions, or even less reconcile its different forces and interests.

Another example of this is the work WORKHORSES (2015), where Östberg Olsson employed a group of unemployed people who, according to the labor market policy at the time, were considered to belong to Phase 3, that is, the last stage before you become insured. In this work, the unemployed's "job" was to play on state-owned Svenska Spel's Jack Vegas machines, which are sometimes called workhorses among players, wearing T-shirts with the same print. They can pick up its t-shirts in the gallery room. As a gallery visitor, you don't know if this is really going on or not. The only thing you encounter in the exhibition room are the contracts between the participants and the artist; contract detailing the playing schedule, payment agreement and the addresses of the bars where the playing took place. There is also a wardrobe with hangers where the unemployed hang their T-shirts when they are not working. A work that created unpleasant, almost absurd connections and conflicts between the political consequences of the so-called line of work and a game-driven economy.

The game economy is something that is also dealt with in an ongoing project that was started around the same time. On the poster for Your Local Gambler (2014-) you can read: "Become a venture capitalist tonight / you invest you get the profit". By staging, among other things, "drum battles", "burn-out competitions" and "wrestling matches", the psychological mechanisms of gambling addiction are investigated. The artist himself takes on the role of bookmaker and organizer, and the audience is transformed into actors with both the power to end the game and to confirm it, but never the ability to stand outside the work of art. At Moderna Museet Malmö, a "drum battle" is arranged where drummers compete to see who can play the longest. The artist himself goes around the audience and collects the audience's bites in this bet in the name of art, in this allegory of our contemporary economy.

When we put aesthetic judgments into words today, we are not limited to the beautiful and the sublime, that is, the terms that are perhaps primarily associated with the origin of aesthetics as a philosophical discipline; children of both enlightenment and colonial modernity. Often, we instead use words like interesting, thought-provoking, sweet, nice, etc. These reviews lack a strong cathartic function. That is, they are relatively mild, hardly revolutionary or shocking. The reason why terms like these have taken over aesthetic judgment is a complicated story. But one of the reasons is likely that the interest of various avant-garde movements in shocking a bourgeois observer has increasingly come to be associated with an anachronistic heroic masculinity and a capitalist predatory drive where shock and disaster have taken on a constitutive function.

Josefine Östberg Olsson's art breaks this norm. But it is hardly a one-way return. The aesthetic category that means the most to her is goosebumps. A physical reaction she associates with a maxed-out electric guitar riff or a revving V8 engine. But as we have seen, her work does not evoke those kinds of effects directly on the exhibition site, but instead places them as a possibility, 'outside the picture', as in the case of Shift into Racing Strip in the Still of the Night.Unlike many other artists who have worked with the rock'n'roll and motorcycle culture we associate with the origins of youth culture in American films such as Rebel Without a Cause by Nicolas Ray and Dennis Hopper's Easy Rider, she has neither an exoticizing, ironizing, documenting or critical scrutinizing relation to its way of life, attributes and rituals. Rather, there is an almost factual relationship to this rebel-related culture that Östberg Olsson is a part of and makes use of in his art, as well as an insistence that even if its attributes have been hijacked and deradicalized, it still carries an ability to hiss and take place even in contexts where it usually does not belong. Maybe that's why - because her works never give the impression of being solely about the contexts the materials for the works are taken from? A feeling that is reinforced by the titles of the works, often formulated in CAPS.

Text by: Fredrik Svens

Art theorist, Akademin Valand, University of Gothenburg

Jonas Silfversten Bergman - 2017

Sandra Mujinga - 2016

Sandra Mujinga's artistry invites you to a contemporary world, a hybrid of clubs, music videos and social media. Her aesthetic expression is attractive; short clip-ins are interspersed with haute couture mixed with musical loops. In the center is a body, sometimes her own, sometimes a family member's, sometimes people browsing images online, sometimes a hired model.

Through performance, video and spatial installations, Mujinga examines how it happens when we "read" what we look at. When we attribute to what we see different meanings and narratives. Her works often direct our gaze towards the background; to everything that surrounds what our gaze would normally be fixed on, and that has a bearing on how we perceive what we see. Here, sounds, objects and movements from different contexts are combined in combinations that manipulate the original narrative and draw our attention and our associations in different directions. Music is an important tool in Mujinga's exploration of visual processes. Many of her works are seductive music videos where the sound takes over and changes how we see what we see. In her performance acts, she often takes on the role of DJ. Through music and visual expressions, she directs people's movements in art rooms or in club environments. Often her musical loops represent the sounds that are part of the background noise that governs our experiences in the physical world. Through the works, Mujinga insists that we become better listeners.

In the video installation and performance act When I Stopped Playing Hard To Get (2015), Mujinga used, among other things, video footage from Congolese weddings she found on YouTube. The wedding photos have, like so much else online, probably been uploaded for private use, to be made available to family and friends. One of the installation's video projections shows excerpts from wedding scenes where different women dance. By replacing the videos' original soundtracks with their own electronic music loops and evocative beats, the experience of the women's dance changes and their movements suddenly create associations with dance styles such as hip-hop or funk.

In many ways, Mujinga's works reflect the visual processes and hybrid genres that spread across the Internet. Where social media sites such as Instagram, SoundCloud, Vine and YouTube have revolutionized the ability to produce and distribute one's own material and thus participate in a wider sense-making.

37

On these digital platforms, specific conditions and time limits apply to the type of material you can post. In the video installation I Gave the World a Word (2016), Mujinga investigates how Instagram and Vine have limitations that affect the conditions of creation and its reception.

Films posted on these sites are designed according to a rule that a video may be no longer than 15 and 6 seconds respectively. In addition, you must consider that your lmade material will be played as a loop. The short format means that the images are more easily distributed on different platforms and can thus reach a wide audience. At the same time, the format causes the lms' information to be compressed, resulting in their original meaning being easily lost when the videos are taken out of context. This means that you as the creator must accept that you will lose control over the video the moment you upload it online and that it can be used by others on social media in relation to completely different types of narratives, thus generating other meanings than the ones you originally intended.

In I Gave the World a Word, Mujinga has produced your pieces of music that are no more than 15 seconds long, thus studying the short seconds of meaning-making in relation to the viewer's perception and experiences. The name of the work is a quote taken from an interview in the music magazine The Fader where Kayla Newman says "I gave the world a word". Newman is known for his video diary on the short lms site Vine. Every day, she records short videos of herself with her cell phone while sitting in the passenger seat of her mother's car. In a six-second long lmloop, she looks contentedly at the shape of her eyebrows in the mobile camera while saying “We in this bitch. Find get crunk. Eyebrows on eek. Da fuq.” The footage became an internet hit and spread across social media. At the time of writing, the video on her Vine account has been viewed over 38 million times. The expression "on eek", which in Swedish roughly means "safe" or "cool", was not an accepted expression before Newman's Vine. After the spread of the video, it has started to be used more and more frequently. I Gave theWorld aWord examines the premises of Instagram and Vine's new formats for creativity and meaning production. The meeting between big business and grassroots movements creates a new type of territory within which new questions arise about copyright, cultural consumption, the private, celebrity, censorship and forms of producing meaning.

Mujinga's performances and video works are rarely about the specific meanings that different visual expressions have. Rather, her work examines the path to the creation of meaning. How the combination of aesthetics, cultural forms, objects, bodies and sounds orients us towards different types of narrative. Her works highlight the potential of mastering the meaning-making process. How one

38

conscious displacement of given meanings can make accessible what at first glance seems difficult to access, alien and strange.

Background

When asked why Sandra Mujinga (b. 1989) wanted to become an artist, she points out that an important part of her career choice was that she was given the opportunity to choose at all, that she had many people who supported her growing up and who still support her. Mujinga was born in Goma in the Democratic Republic of Congo but moved to Norway early on. In 2015, she graduated from the Master's program at the Academy of Arts in Malmö. Today she lives and works in Malmö and Berlin. Mujinga has always been fascinated by thoughts and ideas that do not fully conform to what is accepted. Through her artistry, she gets access to a space to explore the thoughts that make her insecure, things that appear to be crooked, strange or alien.

Karl Patric Näsman - 2016

Text: Ellen Suneson

In Karl Patric Näsman's art, we encounter copies, look-alikes and poor quality. His artistry is characterized by a search for a new type of grammar for art. Within this, the roles of repetition and craftsmanship must be elevated. The skill in imitating an original should be able to become an artistic value in itself.

Two of his latest art projects, Cattle Resting in a Landscape with Riverside Castle and Rainbow Beyond (2012-2015) and Shanghai Pearl Market (2015) show the enormous art copying industry that has grown up in China. In this industry, Chinese artists create imitations of famous works of art commissioned by mainly American and European buyers. The Chinese art copying industry has been sharply criticized in the West, where the paintings are not considered "real" art but are described as mass-produced forgeries. In Cattle Resting in a Landscape with Riverside Castle and Rainbow Beyond, Näsman studies the changing status of artworks on the global art scene. During the course of the project, he contacted a number of different art copying companies in China and ordered copies of a Dutch painting from the 18th century. When he then received the painted copies, he presented them as part of his own art installation. The art installation highlights the paradox of the Western approach to the Chinese art copying industry. At the same time that Chinese artists' imitations of famous works of art are not considered genuine art, there are countless examples of Western artists such as Andy Warhol, Jeff Koons, Sherry Levine or Damien Hirst who also used other people's work and copied other people's work, but who conversely count as some of the most important contemporary artists.

However, the perception that the works painted in the Chinese art copying industry are not real art is not shared by Chinese artists and galleries. Here, the works are instead described as "replicas" and regarded as originals. In the Chinese understanding of the paintings, the concept of shanzhai is central. The word describes the exaltation and passion for the "copy" and the disinterest in the original. In China, shanzhai is very popular and can include, for example, identical copies of mobile phones and branded clothes or people who are look-alikes. Shanzhai is often described as a way for the general public to take part in things that are otherwise only available to a privileged few.

In the art project Shanghai Pearl Market (2015), Näsman together with the Shanghai-based artist Jiang Weitao investigated the shanzhai phenomenon in relation to older traditions of copying and to their own roles as artists. The art project consisted of them jointly performing the act of creating an imitation. Initially, they agreed to use an older imitation technique where paint is applied to copy materials such as marble or granite. They laid out large canvases on the floor in a studio and then started from the technique, which is a kind of splash painting, to produce the copy. The craft was done individually, but they communicated with each other during the work. The result is a surface created with layers of small, different colored paint spots. The relationship between the different colors builds up an image that gives the illusion of a colorful stone material. The collaboration between the two artists can be compared to the process where works are produced in the Chinese art copying factories. There, as a rule, your artists are involved in the work with a copy in order for the execution to be as efficient as possible while at the same time the result must maintain a high level. Although Näsman and Weitao used the same technique, their interpretation of the technique differed. The way in which their expressions differ highlights the fact that the imitation of a work of art is not a mass production but a craft, carried out by human hands.

After the finished imitations, the canvases are cut up and presented both as individual paintings and as a decoration on a folding screen. In the work, the folding screen has a symbolic meaning. The furniture type originally comes from China, where it has been used as a decorative room divider for thousands of years. During the 17th century, many folding screens were imported to Europe and then, in a smaller version, also began to be used with the intention of hiding the body when changing clothes. In the Shanghai Pearl Market, the folding screen gives a clue to the old traditions of copying. Centuries of colonialism, appropriations and migration have contributed to copying having a large impact on image culture throughout history.

The Shanghai Pearl Market was also a way for Näsman and Weitao to explore imitation as a performative act. That is, to examine how copying itself is an act that creates and maintains particular meanings in different contexts. By creating a counterfeit of the rock material marble, it was highlighted how the imitation of certain genuine materials helps to maintain the materials' high status. In addition, it was made visible how repetitive practices in the art world - artistic education, vernissages, exhibition rooms and art criticism - maintain certain stereotypes on which Western art rests. Here you can see how ideas about Chinese mass production and the Western stereotype about the importance of

originality as a condition of artistic value plays a decisive role in how copying techniques are regarded.

Näsman's artistry testifies to a strong interest in how the globalized art scene displaces traditional ideas and meaning systems. The encounters between different cultural meaning systems highlight the individual valuation systems for artistic quality as constructions. Shanghai Pearl Market describes, among other things, how the Western art scene's strong reluctance to regard the copying industry as a cultural expression is a sign that something within its own system is under threat. And how the appreciation of the potential of the copy together with the disinterest in the original and the artistic authenticity is something that threatens the foundations on which the Western art scene rests.

Background

Karl Patric Näsman (b. 1986) originally comes from Örebro. Today he lives and works in Stockholm. In 2015, he graduated from the Master's course in Free Art at Konstfack. Näsman's desire to become an artist was based on a feeling of wanting to think and express himself. Art offered a language that made it easier to explore different things and questions. Today, Näsman appreciates art's ability to always open up to new perspectives, that it is always exciting and constantly offers something new.

André Talborn - 2016

Text: Ellen Suneson

Gestures another word for body language. In that sense, the word describes the movements that people use to reinforce what they say or to communicate without using words. However, in art theory, the term gesture can also be used to explain the content of images. Here the word describes how shapes, colors and details in an image evoke special emotions in the viewer. Historically, artists have wanted to convey different, often conflicting, emotions and messages with their images. The artists in expressionism wanted to depict inner emotional experiences in pictorial form, those in surrealism wanted to capture the unconscious and dreamlike. Minimalism wanted to make art that did not depict anything from external reality at all. Because particular visual elements within the various art directions have been repeated enough times in specific contexts, they have become general gestures that communicate special meanings. This means that it is possible to perceive the meanings of different forms even without in-depth knowledge of art history.

In André Talborn's world of images, he deals with the gestures, rules and meanings of the image in an anarchistic way. Here, a classically painted flower vase can be placed in the middle of an otherwise typically minimalist painting. A tranquil white surface can be broken up by three red lines seemingly painted there in one swift movement with just three brushstrokes. The paintings in the series Superpaintings (2015) balance on the border between image and sculpture. In these, Talborn has combined different shapes and materials so that tension is created on the canvases. This makes the paintings appear three-dimensional while losing their ability to create a direct illusion of reality. The active joining of inconsistent pictorial elements could be read as a mockery of the grand gestures and ideas that have characterized art history. Or as a collage that dilutes the image of all its meanings. But Talborn's artistry conversely shows signs of a great interest in the functions of the image and in the ideas that shaped art history. In his paintings, gestures from different contexts crash onto one and the same surface, thus evoking conflicting emotions that pull the viewer in different directions.

In the painting Taste (2015), the picture surface is divided in the middle by a transverse line. In the lower part of the canvas, white squares placed on a turquoise background create a kind of grid pattern, where black lines in some places follow the outside of the white shapes. The upper part of the canvas is painted with a black base tone that is broken up by quick brushstrokes and splashes of color in gray, blue, pink, green and yellow tones. In the middle of the lower part of the painting is a large watermelon painted in a naïve style. Individually, the gestures in the different parts of the painting are relatively easy to decipher. The pattern in the lower part of the canvas is reminiscent of the geometric shapes of minimalism, the upper part of the emotional expressions of abstract expressionism, and the watermelon of the figurative motifs of naïveté. It is in combination with each other that the content of the painting becomes multifaceted, complex and confused. The placement of the watermelon in the foreground creates a depth in the image that shifts the meanings of the underlying surfaces. The lower part of the image suddenly appears as a table top and its abstract pattern as a decoration on a tablecloth. The upper part of the painting then forms the underlying room where the spontaneous brushstrokes can represent another pattern, those on a wallpaper, or symbolize the movements of the room. At the same time, your options begin to emerge. The geometric shapes of the lower part can be read as a map or as the basis of the well-known computer game Snake where the black lines suddenly take the form of the game's pixelated snakes and dots. The way in which the painting combines pictorial elements from different pictorial traditions makes the visual gestures contradictory and it becomes clear how certain forms are linked to particular feelings or meanings.

The spread of images in the media plays a decisive role in how we see ourselves, others and political or cultural changes. Understanding how visual gestures subtly make us react or feel is therefore not only essential in art theory but is also important to navigating today's fate of images.

Talborn's artistic method is characterized by a strong interest in the complex visual culture in which we live. When he does research for a work, he uses the internet as an equivalent source to the impressions he gets from art exhibitions or books. In front of the computer, he allows the sensations to wash over him and impulsively navigates between different pages, information and images. Then he selects visual details, shapes and colors he is stuck with and allows these to meet on one and the same picture surface. In his artistry, Talborn investigates how humans react to the fierce stream of visual information that shapes today's image culture. The paintings' examination of the functions of the image is a clear example of the important role of art in society at large. Mapping the gestures of images provides important perspectives on the power of visual culture to shape our thoughts, opinions and ideas.

Background

André Talborn (b. 1987) grew up in Växjö. In 2015, he graduated in liberal arts at Umeå University of the Arts. Today he lives and works in Berlin. Talborn's interest in pictures and art was awakened in front of the computer screen in his boyhood room. The small town he grew up in didn't have a big art scene, instead the internet served as a source to access different types of culture. In front of the computer, he was overwhelmed by images and facts, and the opportunity to take part in otherwise inaccessible visual worlds opened up. Talborn works with water- and oil-based paints on canvas. His art reflects a great interest in the digital age and image culture he grew up with.

MARTHA OSSOWSKA PERSSON - 2015

How did you get into art?

I have always drawn and painted, as an only child it was the best pastime. Even as a child I could disappear into drawing for several hours and somehow always wanted to be an artist. It sounds like a cliché, but it really is. The road to art has taken a few detours via art preparation courses to having studied architecture at Chalmers. When I was studying architecture, a teacher asked me why I didn't go to art college. It was like a kind of signal for me and after that there was no other option but to pursue art.

And how did you then find your direction?

At first I worked quite widely with everything from making photo series, painting and drawing to creating animations. But during my first years at art college, my work began to develop in a different direction and I began to move more and more within painting. There I began to explore the relationship between body and flesh. At first it was in contexts where bodies in different states of mind collided and created interesting poses. In my ongoing process, this happens by examining the hand in different compositions and capturing both conscious and unconscious gestures and touches. In my work, the hand is a representation of the body, a tool of the flesh. What is recurring in my works is the meeting, or a confrontation, for example when flesh meets flesh or when a body "communicates" with another body. In painting, I have found a way to combine it with my own physicality.

What is most important about your creation, to you?

Right now, painting is important. In painting, I try to portray. It's like it's growing in layer after layer of paint in an attempt to evoke space for portrayed bodies to move in. It's like I'm looking for an obviousness in the expression. The size of the paintings is important, as a kind of challenge between me and the paper but also in the meeting between the viewer and the subject. When I paint, I use a lot of water, let the paint flow out uncontrollably in puddles, watch it dry, then move the pigments back and forth. Let it dry again. I process the color layers, wash away, start from the traces that bite into the paper. But the creation is not only about the painting itself, but just as much about the process I enter into and the ideas behind my work. I have always seen myself as a storyteller who tries to challenge myself and different notions that exist around us. For me, it's like the questions I ask myself through painting come out and are tested in the room. Right now I paint women's hands, based on myself as a woman and my way of looking. A kind of inherent curiosity about the bodily landscape and conventions. For me, it's like an ambivalent balancing act where I oscillate between the seductive and beautiful to the fragile and violent, it becomes like a close-up image that in turn becomes an abstraction. That breaking point is very interesting to me and somehow it reinforces the complexity that exists and that we experience in our bodies.

IDA PERSSON - 2015

How did you get into art?

As a child I loved to draw and paint. I said even then that I wanted to be an artist, but the older I got, the more unrealistic it felt that you could make a living being an artist. But after high school I decided to give it a year at preparatory art school. One year turned into three years and eventually five years at university. Every year the feeling that this is what I wanted to do grew stronger.

And how did you then find your direction?

After trying different mediums and techniques for a few years, I started to understand what I was interested in and found a working method that worked for me. I was then able to develop this during my time at art school through disciplined work and the guidance and support of professors and with students.

What is most important about your creation, to you?

Through my creation, I can work with subjects I find important and interesting while having a lot of fun. Art is a complex tool with which one can deal with complex issues without simplifying. You can tell several stories at the same time, incomplete and contradictory. They can be based on facts or completely subjective experiences and one is under no obligation to stick to the subject.

Interview: David Stenbeck

IDUN BALTZERSEN - 2015

How did you get into art?

I don't know how it really started, it's more like I never stopped. My mother is also an artist and I have always had great respect and reverence for becoming an artist, and that that profession existed as a real possibility has always been obvious to me. I have been drawing all my life; when I was a kid, one of my favorite motifs was my parents' orange Citroen 2CV, and it has continued into adulthood.

And how did you then find your direction?

After basic education, I entered the Bergen Academy of Arts in the Bachelor's program with a focus on graphic studies, where I received a very good introduction to all techniques imaginable in terms of craftsmanship. After I learned to handle everything properly, I became increasingly clear about what interested me and what focus my artistry should have. I am very happy that I chose to study at Konstfack and take my master's. There I was introduced to a clearer way of working with my art, which is also easier to convey linguistically, something that comes in handy when writing applications.

What is most important about your creation, to you?

For me, it is very important to feel that I go to my work, and have a job that is meaningful, and that the work is always full of pleasure. Therefore, I always have points of reference, regardless of whether it concerns exhibitions or the deadline for an application. I can appreciate being seen, that the outside world notices me. I often justify my works based on how young girls have been depicted throughout the ages, and then of course it is good if this reaches the viewer, but I am satisfied if it somehow hits a nerve, that it is experienced as something surprising. You get a sense of something unexpected.

Interview: David Stenbeck

PAUL FÄGERSKIÖLD - 2013

The most difficult thing an artist can do today is perhaps to use just paint and brush on canvas. What remains to be done with painting as a medium? Paul Fägerskiöld succeeds in both recapturing and developing the art of painting by combining sensuality and intellect in one and the same painting. It's perfectly fine to just be seduced, just as you can devote yourself for hours to intelligent references to other paintings. In a remarkable way, Fägerskiöld cancels the boundary between emotion and reason.

Gabriel Karlsson - 2021

This year's fellow works mainly with sculpture that balances between the abstract and the concrete. The works are executed with enormous precision and feeling for the material's properties and composition. In his artistry, the fellow combines the slow and traditional craftsmanship with a conceptual thinking that challenges the viewer to reflect on the sculpture and the objects' ability to be between an inner and an outer space.

The 2021 scholarship is awarded to: Gabriel Karlsson, Malmö Academy of Arts.

IN CONVERSATION WITH GABRIEL KARLSSON

Iselin Page, Curator Artipelag:

Now I'm almost covered in snow in my apartment and switch between looking at your portfolio and looking out the window at the winter landscape. Everything suddenly feels white and quiet. Outside, the landscape opens up, the light penetrates the white sky and the snow pours down at a rate reminiscent of a steady but slow process. When I turn my gaze to the objects in the portfolio, my mind is calm. In your last email you briefly described how you work with slow thought processes and materials, how you use this as a method to slow yourself down. Would you like to tell us a little more about what the work process looks like and how the material and the idea intertwine, and how they influence each other?

Gabriel Karlsson:

I am also sitting covered in snow in the winter landscape. Working with material that requires time is for me a way to slow down thought, sometimes to the point that it ceases to exist or changes form. By blurring the boundaries between me and what is in front of me, a way of thinking is created that contrasts with a habitual view and idleness. In the studio I try to listen to the material and the object's own will rather than controlling it, and I often work on many projects at the same time to let them flow in and out of each other. Although I have power over what happens when I construct conditions and frameworks for projects, I rarely feel that I am the one who decides when something has actually taken shape. At that stage, I'm probably as much an observer of what's in front of me as anyone. Although the work process often seems slow in the studio, it also happens in parallel with a faster thought process that is outside the practical work. It is related to observations in everyday life that I want or need to bring into the studio. My interest in sculpture is very much based on how consciousness relates to the environment and how we create ghost images of what we see within us. These constructed images in the mind are actually at least as real as what exists outside of us. If one accepts a distinction between two different types of object, the actual and the imagined, then I think that sculpture has the ability to be in the middle between these two modes.